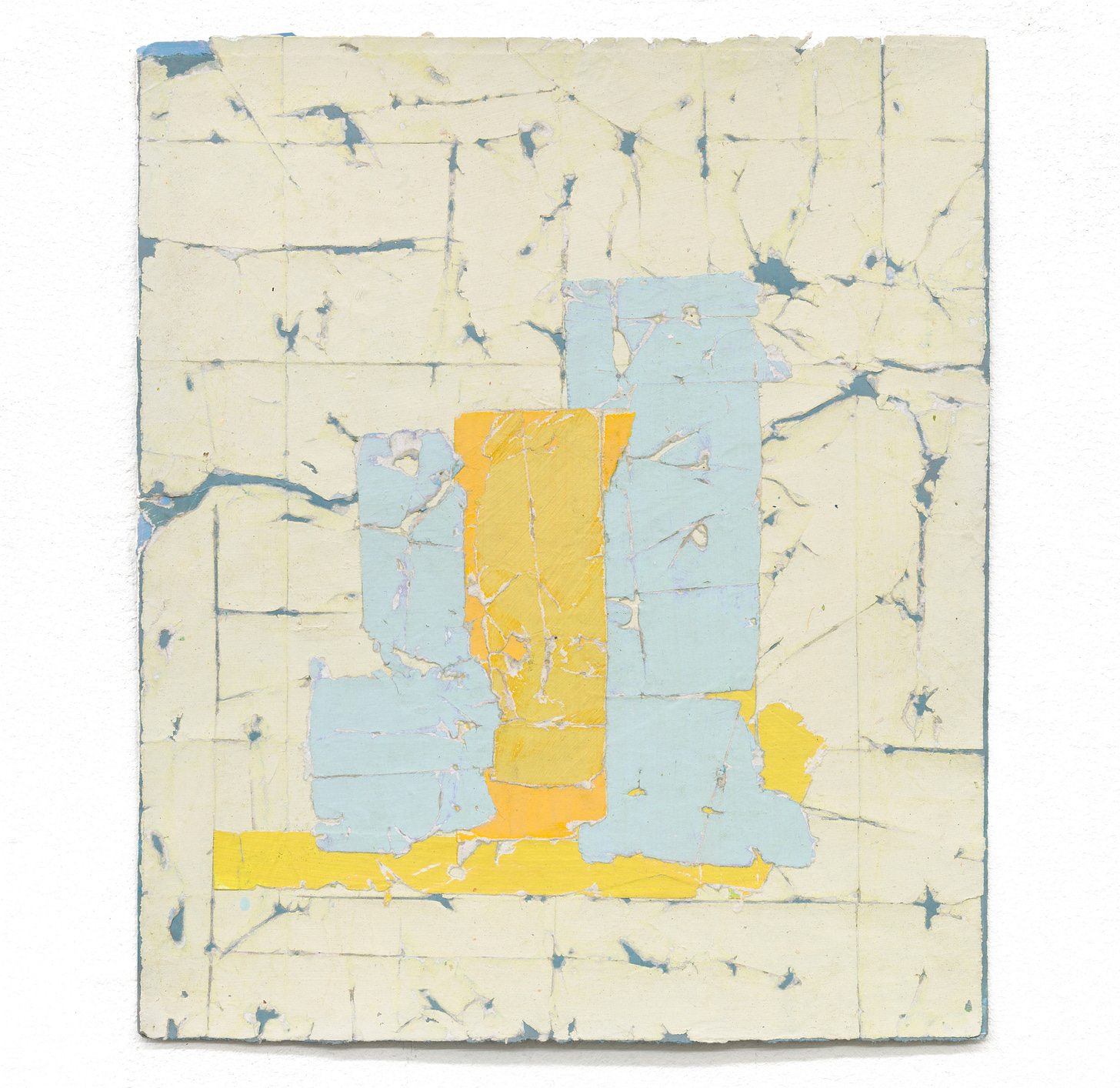

I’ve been excited to speak to Antoine Langenieux-Villard for some time now. The French artist, like myself, works between painting and collage. I find his colour palette especially alluring, how he chooses closely related colours that are sometimes lighter or darker versions of each other. His compositions are fairly minimal, and I love how the blocks of colour are never solid; they’re broken up by lines or cracks. It’s hard to tell, but the surface is textured and scattered with tiny details that I notice when I zoom in on my phone.

I could tell Antoine had a fascinating process. I wasn’t entirely sure how he was achieving such beautifully distressed surfaces, although I did read something on Instagram that spoke of a process involving folding a cotton surface, I think, before the paint had dried.

Anyway, I wanted to hear him explain it himself, so I asked Antoine - who’s currently based between Paris and Normandie - if he’d be up for some nerdy questions, and he kindly said yes.

Hey Antoine. I was curious to see that folding plays a big role in your work. Can you explain that? Do you paint a surface and then fold it before it dries?

The paintings are made on the ground, off the stretcher, bathed in successive colored waters, then folded. I often leave them to dry in piles, tied up with ropes then unfold them later. The process is autonomous, I only observe the results from the previous actions. The works in progress lay on the floor, get pinned onto the walls and gather at different stages until the final assemblage.

Are all the lines I see in your work mostly edges where folds meet?

The first lines appear when I unfold the support; they’re the starting point of construction. I use sandpaper and these lines guide me, later by necessity other lines appear where different pieces of material are assembled together, either through collage or sewing.

When you work on cotton, are you gluing paper onto the surface or sewing the paper, or is that only in your smaller paper collages?

I don’t use paper in my paintings, it’s only paint on cotton. At first though, the abrasive technique came from an experience with paper, which is still ongoing. Those paper collages made me challenge the way I was using my material when painting.

The sewing comes from the necessity to repair and strengthen the surface from previous manipulations. However, they differ to a collage piece, as the sewn line shows a tension and signifies a specific flatness when the painting is stretched. This method of assemblage leaves me in the studio with an abundant source of material, residues of previous paintings, cut-outs that have taken place over the years. The sewing allows me to reunify those different fragments onto the same plane.

Sometimes painting with brushes can feel a bit contrived. What do you like about withdrawing the role of your hand in this way? It looks like your marks are mostly from folds and the broader process of constructing the piece.

I think about the gesture and its inscription on the surface through different methods of assemblage and folding. These are strategies that withdraw the role of my hand and allow me to avoid any preconceptions. Removing the eye-hand brush combination helps challenge the way forms can emerge.

Two stories have accompanied me when I think about painting. The first one is about Matisse, asking his students if they want to paint. He told them that if that is what they desired then "First of all, you must cut out your tongue, because your decision takes away the right to express yourself in any other way than with your brushes". Simon Hantaï builds on Matisse's adage, adding that painting must be done "alone, as if the painter were blindfolded and with his arms cut off".

This attitude of withdrawal conditions the act of painting. The body bent towards its own necessity. One must think through gestures, where the trace and its materiality are the absolute signifiers: they fix a sensation.

Can you tell me how else you attack the surface? It looks quite distressed like you’re using sandpaper.

I replaced the brush with sandpaper and the surface really deteriorates over time because of the successive manipulations. This allows me to remove and excavate the surface, scratching into the thickness of the support, which is the opposite of using a brush to add layers. This fragility leads me to restore and repair the support, which again becomes a gesture of necessity, allowing me to remove myself and stay at the service of the object of painting: to take care of its flatness.

I’ve always loved your colour palette, especially how you use different hues of the same colour, like two different greens together. Is there anything behind that decision or is it just what you're compelled by?

I’ve always celebrated colours and their importance for producing a sensation that’s non verbal but I don’t use any rule, the decisions come while making, intuitively.

There’s also subtle bits of colour that look like former layers underneath the main colour. Is that what happens when you peel the folds after the paint dries?

All the layers reappear when I unfold the fabric. From the first layers - I often start with a black cotton, to the gesso and multiple layers of dyed cotton. Lastly, the final touches include a colour, which comes from the fabric bandages that are collaged at the reverse side of the surface. They repair the holes and tears from the sandpaper and other manipulations. They are important colour confrontations; where both the front and the back of the painting are visible on the same plane. These little hints of color make the surface vibrate.

I was happy to see you do something I do, which is recycle materials from previous works in new works. What do you like about doing that?

To repair and recycle act as a third hand, which has no desire but to state the surface as a membrane, where both the reverse side and and the front are active even if not visible. What is behind, under or hidden, remains active.

Recycling material comes with the same idea that painting must be made on its own, from its own making within an autonomous process. I also like the idea that when you look at the surface it forms a unity but from different temporalities. It allows me to reassess the work. It’s like an excavation from the studio, made from heterogeneous elements, from different years.

Making these paintings has created a philosophy that informs the way I live and my domestic life: I repair, re-use and repurpose and look to references such as in rural France where you see large barns and doors be repaired, with different materials, such as a metal plate on a wooden door.

Lastly, are there any shows you want to plug?

I have a couple of upcoming shows in 2025, including ‘Art on Paper’ in Milan, and a solo show at Loom Gallery.

Follow Antoine on Instagram: @antoinelangenieuxvillard

Things on Our Radar This Week

Things are pretty quiet right now before the Christmas break, but Hauser and Wirth put out a great video on Jack Whitten’s solo show, featuring artists and tutors interrogating the work

White Cube also released a great video interview with Tracey Emin talking about her brilliant show in Bermondsey

The Best Painting Shows in London This Month

Mary Ramsden at Pilar Corrias (ends 11 Jan)

Joan Snyder at Thaddeus Ropac (ends 5 Feb)

Ana Monso’s paintings at Saatchi Gallery (ends 12 Jan)

Gabriel Hartley at Seventeen Gallery (ends 21 Dec)

Charlotte Winifred Guérard at Palmer Gallery (ends 21 Dec)

Thanks for reading, see you next time!

Oliver & Kezia xx

Palette Talk is free and we hope to grow with your support. If you’ve enjoyed reading, drop us a donation via PayPal…