The Uniquely Beautiful Woven Paintings of Julia Bennett

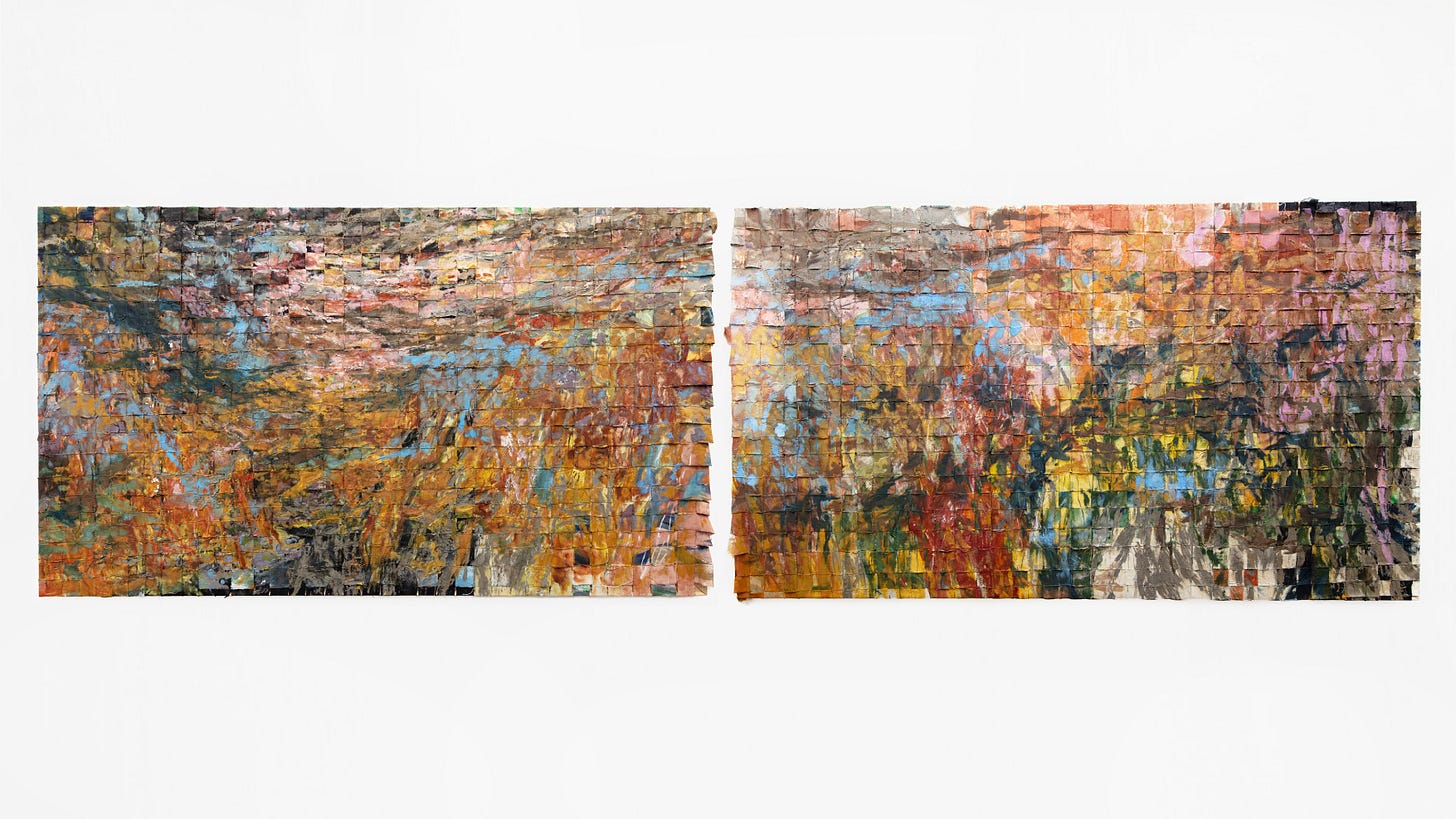

While I do discover a lot of artists on Instagram, I’m happy to say I discovered Julia Bennett’s work in real life. I had walked into Union Pacific gallery to check out a group show I knew little about. Julia’s work caught my eye first. Her pieces used grids but they were expressive; ordered yet painterly.

I walked around one of her paintings and discovered splashes of colour on the side. The piece was earthy and chunky, as if it had been sculpted at a quarry. I didn’t quite know what I was looking at, how she made it, what materials she was using, but I loved the textures and the intrigue she managed to conjure. I thought: Here’s an artist who’s discovered her own unique way of creating.

I eventually reached out to Julia, who’s based in Southern California but studied her MA at the Royal College of Art here in London. I was curious about how she made her paintings and her use of materials that aren’t even on most artists’ radar.

Hey Julia. Can I call your pieces woven paintings? How would you describe them?

Woven paintings, re-woven paintings - I’m not sure if I’ve found the right words for them myself yet, but I would describe them as woven processes. They remain in a tireless state of flux, bodies of found materials, combining past and present in order to find a future.

My work is always finding concern with its own state of permanence, so it’s constantly shifting in physicality. By tearing unresolved paintings down into strips to be re-integrated into a new form has become a practice that forces slowness and makes room for disruption of repetition.

I caught some of your work at Union Pacific. Your pieces really felt like 3D paintings, quite chunky, with splashes of colour on the side. How do you make them?

For some backstory, during my MA at the RCA, a large part of my practice included experimenting with alternative surfaces, namely mycelium bio-composites. These pieces felt more like lichen-coated artifacts, which I was instantaneously drawn to. Then came my affair with river mud and clay, which began on a residency in the Netherlands (CloverMill Artist Residency).

After the use of foraged soil and clay became integral to my work, I wanted my more traditional paintings to retain an element of that. These pieces are thick, layered in pigment, built up with clay, often collaged with other material. I find myself scraping layers off and re-applying until, in some way, the piece reveals itself to me. I’d rather they felt more kindred to objects than to two-dimensional paintings.

I noticed you’re using things like foraged clay and earth pigment, which I rarely see other artists use.

I use a wide variety of materials. As some of my weavings have been made from oil paintings, I have to use oils when adding to those fragments. But my favourite way to paint is with foraged pigment. Now that I’m based in Southern California, I’ve been collecting a lot of soft stone pigments, namely ochre and sandstone. But I love making dyes and inks from oak galls, acorns, red alder bark, elderberries, yarrow, and stinging nettle – most of which have inherent medicinal properties that I also use for homeopathic remedies. Dyes that I’ve been eager to try are the Northern Red-Dyes (Dermocybe sanguinea) and Hawk Wings (Sarcodon imbricatum) mushrooms.

I was curious about the grids. Do they offer you a structure in which you can anchor the more playful and expressive marks?

Most definitely. The splinters of each earlier painting act like a skeleton, but the obscurity of the grid creates an illusion of a pixelated image. Once I’ve finished re-weaving each work, I take my time to find the new visual, usually a blurred landscape, and that becomes my new direction. Each painting more and more resembles a mishmash of research on the precolonial ecology of ‘California’ and present-day experiences of super blooms or decay. Honestly, they’re almost impressionistic of the San Bernardino chapparal zones at this point. But because of this juxtaposition and the fragmentation of the grid, I’m able to jump from one expression to another and maintain the rhythm. Rage, beauty, grief, and healing all coalesce in these webs.

Your titles reference life and death; is there a philosophical examination woven in there too?

My practice has become a sort of ritual: a way to see, to grieve, to question reality and the repetition of history, as well as a way to find potential futures and explore remediation. Life and death are essential components to this.

My work is consumed by the paradox of ongoingness. So when I’m assembling these paintings, my mind flutters from encounters with (my constant witness) the red-tailed hawk gliding above, to finding her broken along the roadside. Or seeing the white and red speckled valleys of Buckwheat overgrown with hostile, combustible mustard, but then, finding the previously mustard-congested hills filling back up with Brittlebush and Mojave Yucca. There are profound impacts happening, both negatively and positively, it’s crucial to be very conscious of both.

Ultimately, I want my work to serve as a reminder of our impossible present; a time of rupture, ghosts, and remembrance guiding us to decolonization and metamorphosis.

Follow Julia on Instagram: @juliabennett___

Things on Our Radar This Week

The ‘Towards the Light’ show at Gallery Rosenfeld, which spotlights artists concerned with the colour white

Plaster mag asks the question, What’s the point of a curator?

Fiber art is having a moment; an interesting look at how the commercial view of fiber artists is changing

Robert Nava has a solo show in Madrid

An illuminating piece on the dearth of studio space in London, not to mention rising costs for artists

Thanks for reading, see you next time!

Oliver & Kezia xx

Palette Talk is free and we hope to grow with your support. If you’ve enjoyed reading, drop us a donation via PayPal…